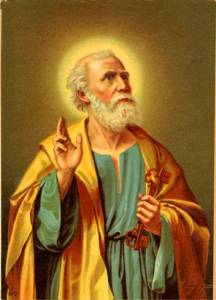

THE CONFESSION OF ST. PETER THE APOSTLE

January 18, 2018

Chapel of the Apostles

Sewanee, Tennessee

Readings: Acts 4.8-13, Psalm 23, I Peter 5.1-4, Matthew 18-19

For a video of the sermon, click here.

Tonight we hear two straightforward questions. First, Who do people say that the Son of Man is? Some say you’re John the Baptist. Others say you’re Elijah, or maybe Jeremiah or one of the prophets. But then Jesus ups the ante. But who do you say that I am? The theorizing is over. Jesus is staring into the eyes of these men, his friends and disciples, who had followed him around, heard him teach, seen him heal, been amazed and confused and bewildered. After all of this, who do you say that I am? Maybe it was like those moments in class, when the professor asks a question that seems so obvious on one level, almost rhetorical. Except it’s not a rhetorical question–they want a real answer, and they’re looking at you, but you can’t quite form the words, so you pretend to scribble something down in your notebook and hope they move on to the next person in the row? But who do you say that I am? St. Peter speaks up for the twelve, speaking those words that God had written on his heart, had placed on his lips: You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God.

It is a divine revelation. Jesus is not only a wisdom teacher or preacher of peace. He is not only a healer and worker of wonders. He is not only a teacher of the Law who proclaims the Kingdom of God. Beneath the teachings, the sayings, the signs, there is a deeper reality–a reality to which all of these things point. He is Messiah. He is the Son of God. He is Lord. Such a confession is a gift from God. It is the foundation of the Church, and it is our gift today.

Our modern ears can miss, however, the radical and inherently political nature of this confession. Messiah invokes a whole history of expectation, of hoping for deliverance from the violence of political oppression. Son of God is just as political. It was a title Caesar had taken for himself–Caesar, Son of God, Savior of the World. To say Jesus was Messiah and the Son of the living God set Jesus up against Rome. It set his followers up against Caesar. In a world dictated by the fist of Rome, where peace and order were brought and maintained by brutality, terror, fear and violence–in such a world, Peter is confessing a deeper reality. He is confessing the central reality of the cosmos: Jesus is Lord. And in so doing, he is rejecting the power of Empire, the power of Caesar, and casting them down as idols. He is rejecting this power, and confessing the power of God, the power of Love Divine, and, though he does not know it yet, the power of the cross.

Who do you say that I am? This is not a moot question today. On the contrary, it could not be more relevant. In the face of war, violence, oppression, fear, and evil, we are asked the same question: Who do you say that I am? What reality will we confess? Will Empire encroach on the Kingdom of God, Caesar on the sovereignty of Christ? Never.

Some friends and I once visited eastern France to see the battlefields of World War I. We stopped in a small village where a museum of the Great War was located, but it was lunch, so in typical French fashion, everything was closed for two hours. Knowing that we had limited time there, we set off to grab a panini and do a small walking tour of the village. When I bought the panini, I asked the vendor to point me to the church, an obvious first stop for me. He pointed me down a small, downhill road sandwiched between tiny shops. In no time we came to the edge of the village, and there was the small stone church, situated at the edge of town, which is unusual for any French town I have ever visited. The church was in a field, just beginning to sprout green with the Spring weather. But not the field next to it. Its soil had this chalky look. Nothing seemed to be growing. And I noticed that all the countryside was checkered with these chalky fields between green fields. Across the street from the church, there was a barbed wire fence, with the same chalky soil. Inside were small trees and bushes, each with thorns wrapped around them, choking them. And on the fence, a sign: “Do not enter. Danger of death.” On the other side of this fence among the thorns, I read, it was possible that there was still live ammunition on the ground, waiting to be disturbed, waiting to fulfill its evil purpose, live ammunition from the Great War 100 years ago.

The small stone church had been destroyed during the Great War. It used to be in the middle of town, like in all small towns in France. But after the War, they decided to rebuild it here, where trenches had once snaked their way across the field; where the soil seemed useless, unable to recover; where live rounds of ammunition still lurked about; where Death and War seemed to reign. In the middle of all of this, a small stone church.

The small church pointed to something deep, something true. There was a deeper cosmological reality than Empire and War. Death and Evil, even at that darkest moment, did not reign. Jesus Christ reigns. God has the last word. And to that, the Church is a witness.

Who do you say that I am? We say that you are the Messiah, the Son of the living God, who dying and rising destroyed the power of sin and death, and led captivity away captive. But in the aftermath of the war, in the face of such destruction and death, surely such a confession was hard. Maybe it was only a whimper, a whisper of hope. So it seems with us sometimes. We confess that Jesus is Lord, but some days it is easier than others. And over our lifetimes, it is a confession we grow into, day by day, by the grace of God and the power of the Holy Spirit.

As I was walking out of the church, I ran into a woman. I asked her for directions, and she pointed us to our destination. My accent gave me away as a foreigner, though: “You’re Canadian, aren’t you?” She asked if I liked the church. Her grandfather had helped rebuild it after the War. He came back scarred, she said. He was a gueule cassée, one of those words you read in French literature or history books. Roughly translated, it means broken face, except gueule is only used for animals, like dogs. These were men who came back with unrecognizable faces, disfigured because of injuries in the war—some 15,000 Frenchmen in World War I alone. When he came back, all he wanted to do was rebuild the church, she said. He couldn’t let the war have the last word.

What a confession—a confession of the power of God, the power of Love Divine. Despite his brutal experience with war, his actions were a confession that Empire and Death were not Lord, but Jesus is Lord. Sin and Evil do not reign, but Christ reigns. Maybe it was a whimper at first, but I would like to think that with every stone his confession grew stronger and stronger, each stone squashing the power of Hell, a Hell already vanquished by the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

We do not approach life with a naivete that refuses to see the evil in the world or in our lives. We are not blind to sin and the effects of sin. Yes, we see–we experience sin and evil in a real, even personal, way. But we know that it does not have the last word. Our lives are a testimony that God has the last word. Our lives are a confession that Jesus is Lord. Like each stone of that small church in the battlefield, each day of our lives builds up and upon the witness of the Church, squashing the very power of Hell.